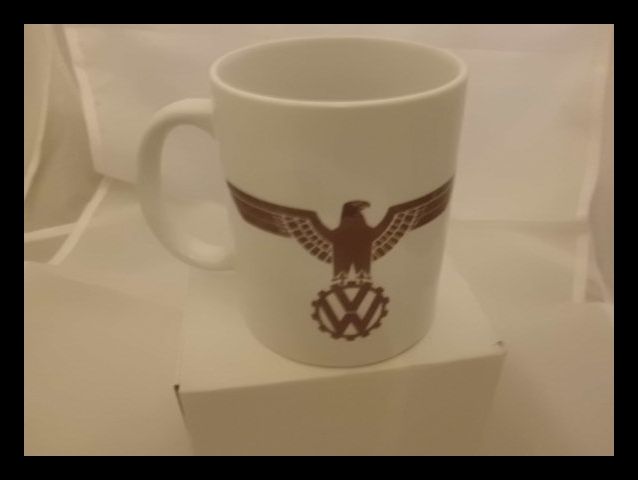

WW2 VW voltswagen printed mug

11oz dishwasher safe mug

Volkswagen was originally established in 1932 by the German Labour Front (Deutsche Arbeitsfront) in Berlin. In the early 1930s, the German auto industry was still largely composed of luxury models, and the average German could rarely afford anything more than a motorcycle. As a result, only one German out of 50 owned a car. Seeking a potential new market, some car makers began independent "people's car" projects – the Mercedes 170H, Adler AutoBahn, Steyr 55, and Hanomag 1.3L, among others.

The trend was not new, as Béla Barényi is credited with having conceived the basic design in the mid-1920s. Josef Ganz developed the Standard Superior (going as far as advertising it as the "German Volkswagen"). In Germany, the company Hanomag mass-produced the 2/10 PS "Kommissbrot", a small, cheap rear engined car, from 1925 to 1928.Also, in Czechoslovakia, the Hans Ledwinka's penned Tatra T77, a very popular car amongst the German elite, was becoming smaller and more affordable at each revision. Ferdinand Porsche, a well-known designer for high-end vehicles and race cars, had been trying for years to get a manufacturer interested in a small car suitable for a family. He felt the small cars at the time were just stripped down big cars. Instead he built a car he called the "Volksauto" from the ground up in 1933, using many of the ideas floating around at the time and several of his own, putting together a car with an air-cooled rear engine, torsion bar suspension, and a "beetle" shape, the front hood rounded for better aerodynamics (necessary as it had a small engine).

VW logo during the 1930s, initials surrounded by a stylized cogwheel and swastika wings

In 1934, with many of the above projects still in development or early stages of production, Adolf Hitler became involved, ordering the production of a basic vehicle capable of transporting two adults and three children at 100 km/h (62 mph). He wanted all German citizens to have access to cars.[6] The "People's Car" would be available to citizens of the Third Reich through a savings plan at 990 Reichsmark ($396 in 1930s U.S. dollars)—about the price of a small motorcycle (the average income being around 32 RM a week).

Despite heavy lobbying in favor of one of the existing projects, it soon became apparent that private industry could not turn out a car for only 990 RM. Thus, Hitler chose to sponsor an all-new, state-owned factory using Ferdinand Porsche's design (with some of Hitler's design constraints, including an air-cooled engine so nothing could freeze). The intention was that ordinary Germans would buy the car by means of a savings scheme ("Fünf Mark die Woche musst du sparen, willst du im eigenen Wagen fahren" – "Five marks a week you must put aside, if you want to drive your own car"), which around 336,000 people eventually paid into.[10] However, the entire project was financially unsound, and only the Nazi party made it possible to provide funding.

Prototypes of the car called the "KdF-Wagen" (German: Kraft durch Freude – "Strength through Joy"), appeared from 1938 onwards (the first cars had been produced in Stuttgart). The car already had its distinctive round shape and air-cooled, flat-four, rear-mounted engine. The VW car was just one of many KdFprograms, which included things such as tours and outings. The prefix Volks— ("People's") was not just applied to cars, but also to other products in Germany; the "Volksempfänger" radio receiver for instance. On 28 May 1937, Gesellschaft zur Vorbereitung des Deutschen Volkswagens mbH ("Company for the Preparation of the German Volkswagen Ltd."), or Gezuvor for short, was established by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront in Berlin. More than a year later, on 16 September 1938, it was renamed to Volkswagenwerk GmbH.

VW Type 82E

Erwin Komenda, the longstanding Auto Union chief designer, part of Ferdinand Porsche's hand-picked team, developed the car body of the prototype, which was recognizably the Beetle known today. It was one of the first cars designed with the aid of a wind tunnel—a method used for German aircraft design since the early 1920s. The car designs were put through rigorous tests, and achieved a record-breaking million miles of testing before being deemed finished.

The construction of the new factory started in May 1938 in the new town of "Stadt des KdF-Wagens" (modern-day Wolfsburg), which had been purpose-built for the factory workers.[13] This factory had only produced a handful of cars by the time war started in 1939. None were actually delivered to any holder of the completed saving stamp books, though one Type 1 Cabriolet was presented to Hitler on 20 April 1944 (his 55th birthday).

War changed production to military vehicles—the Type 82 Kübelwagen ("Bucket car") utility vehicle (VW's most common wartime model), and the amphibious Schwimmwagen—manufactured for German forces. As was common with much of the production in Nazi Germany during the war, slave labor was utilized in the Volkswagen plant, e.g. from Arbeitsdorf concentration camp. The company would admit in 1998 that it used 15,000 slaves during the war effort. German historians estimated that 80% of Volkswagen's wartime workforce was slave labor.[citation needed] Many of the slaves were reported to have been supplied from the concentration camps upon request from plant managers. A lawsuit was filed in 1998 by survivors for restitution for the forced labor. Volkswagen would set up a voluntary restitution fund.

Volkswagen factory

1945–1948: British Army intervention, unclear future[edit]

The company owes its post-war existence largely to one man, wartime British Army officer Major Ivan Hirst, REME. In April 1945, KdF-Stadt and its heavily bombed factory were captured by the Americans, and subsequently handed over to the British, within whose occupation zonethe town and factory fell. The factories were placed under the control of Saddleworth-born Hirst, by then a civilian Military Governor with the occupying forces. At first, one plan was to use it for military vehicle maintenance, and possibly dismantle and ship it to Britain. Since it had been used for military production, (though not of KdF-Wagens) and had been in Hirst's words, a "political animal" rather than a commercial enterprise[citation needed] — technically making it liable for destruction under the terms of the Potsdam Agreement — the equipment could have been salvaged as war reparations.[citation needed] Allied dismantling policy changed in late 1946 to mid-1947, though heavy industry continued to be dismantled until 1951.

One of the factory's wartime 'KdF-Wagen' cars had been taken to the factory for repairs and abandoned there. Hirst had it repainted green and demonstrated it to British Army headquarters. Short of light transport, in September 1945 the British Army was persuaded to place a vital order for 20,000 cars. However, production facilities had been massively disrupted, there was a refugee crisis at and around the factory and some parts (such as carburetors) were unavailable. With striking humanity and great engineering and management ingenuity, Hirst and his German assistant Heinrich Nordhoff (who went on to run the Wolfsburg facility after military government ended in 1949) helped to stabilize the acute social situation while simultaneously re-establishing production. Hirst, for example, used his fine engineering experience to arrange the manufacture of carburetors, the original producers being effectively 'lost' in the Russian zone.The first few hundred cars went to personnel from the occupying forces, and to the German Post Office. Some British Service personnel were allowed to take their Beetles back to the United Kingdom when they were demobilised.

In 1986, Hirst explained how it was commonly misunderstood that he had run Wolfsburg as a British Army major. The defeated German staff, he said, were initially sullen and unresponsive, having been conditioned by many years of Nazism and they were sometimes unresponsive to orders. At Nordhoff's suggestion, he sent back to England for his officer's uniform and from then on, had no difficulty in having his instructions followed. Hirst can be seen photographed at Wolfsburg in his uniform, although he was not actually a soldier at the time but a civilian member of the military government. The title of 'Major' was sometimes used by someone who had left the Army as a courtesy,but Hirst chose not to do so.

The post-war industrial plans for Germany set out rules that governed which industries Germany was allowed to retain. These rules set German car production at a maximum of 10% of 1936 car production.[19] By 1946, the factory produced 1,000 cars a month—a remarkable feat considering it was still in disrepair. Owing to roof and window damage, production had to stop when it rained, and the company had to barter new vehicles for steel for production.[citation needed]

The car and its town changed their Second World War-era names to "Volkswagen" and "Wolfsburg" respectively, and production increased. It was still unclear what was to become of the factory. It was offered to representatives from the American, Australian, British, and French motor industries. Famously, all rejected it. After an inspection of the plant, Sir William Rootes, head of the British Rootes Group, told Hirst the project would fail within two years, and that the car "...is quite unattractive to the average motorcar buyer, is too ugly and too noisy ... If you think you're going to build cars in this place, you're a bloody fool, young man. The official report said "To build the car commercially would be a completely uneconomic enterprise."In an ironic twist of fate, Volkswagen manufactured a locally built version of Rootes's Hillman Avenger in Argentina in the 1980s, long after Rootes had gone bankrupt at the hands of Chrysler in 1978—the Beetle outliving the Avenger by over 30 years.

Ford representatives were equally critical. In March 1948, the British offered the Volkswagen company to Ford, free of charge. Henry Ford II, the son of Edsel Ford, traveled to West Germany for discussions. Heinz Nordhoff was also present, and Ernest Breech, chairman of the board for Ford Motor Company. Henry Ford II looked to Ernest Breech for his opinion, and Breech said, "Mr. Ford, I don't think what we're being offered here is worth a dime!"Ford passed on the offer, leaving Volkswagen to rebuild itself under Nordhoff's leadership

1948–1961: Icon of post war West Germany

1949 Volkswagen "split rear window" Sedan

Volkswagen Cabriolet (1953)

Volkswagen Type 2 (T1)

An original 1300 Deluxe, circa 1966.

In the later 1960s, as worldwide appetite for the Beetle finally began to diminish, a variety of successor designs were proposed and, in most cases, rejected by management.

From 1948, Volkswagen became an important element, symbolically and economically, of West German regeneration.[according to whom?]Heinrich Nordhoff (1899–1968), a former senior manager at Opel who had overseen civilian and military vehicle production in the 1930s and 1940s, was recruited to run the factory in 1948. In 1949, Major Hirst left the company—now re-formed as a trust controlled by the West German government and government of the State of Lower Saxony. The "Beetle" sedan or "peoples' car" Volkswagen is the Type 1. Apart from the introduction of the Volkswagen Type 2 commercial vehicle (van, pick-up and camper), and the VW Karmann Ghia sports car, Nordhoff pursued the one-model policy until shortly before his death in 1968.

Volkswagens were first exhibited and sold in the United States in 1949, but sold only two units in America that first year. On entry to the U.S. market, the VW was briefly sold as a Victory Wagon. Volkswagen of America was formed in April 1955 to standardise sales and service in the United States. Production of the Type 1 Volkswagen Beetle increased dramatically over the years, the total reaching one million in 1955.

The UK's first official Volkswagen Importer, Colborne Garages of Ripley, Surrey, started with parts for the models brought home by soldiers returning from Germany.