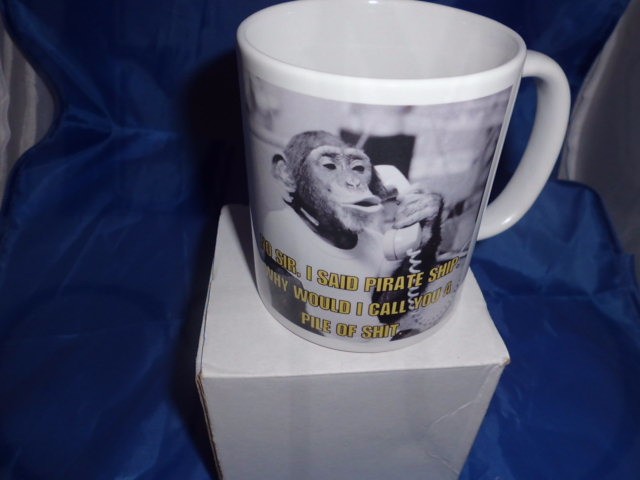

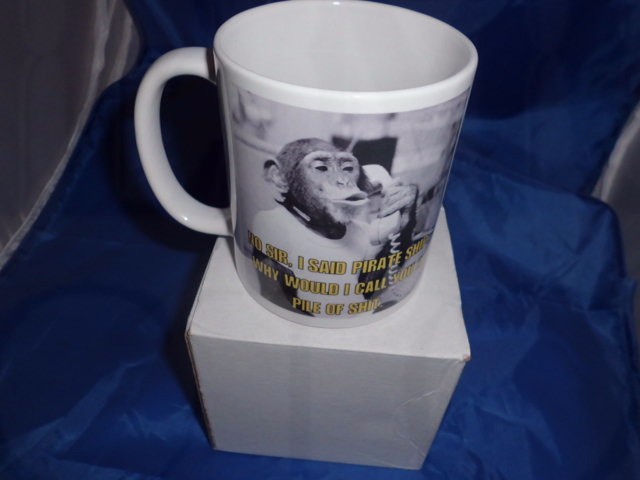

No sir i said pirate ship why would i call you a pile of Sh#t personalised mug

11oz dishwasher safe mug same image on the opposite side

The mugs we use are top quality bright white, Orca coated, and are Dishwasher and Microwave safe, the high quality images are bonded into the surface of the mug, and do not fade or peel off like transfers

GREAT FOR GIFTS, BIRTHDAYS, OR JUST TO ADD TO YOUR MEMORABILIA COLLECTION.

The artwork is created in our offices/workshop, and we are available for custom work. These designs are individually made, not mass produced.

Please note that I take great care in packaging the mugs they are sent in a polystyrene mug box designed to specifically for posting mugs hence the postage costs

Cheeky monkey

Non-human primates don’t just laugh – there is evidence they can crack their own jokes. Koko, a gorilla in Woodside, California, who has learned more than 2000 words and 1000 American Sign Language signs, has been known to play with different meanings of the same word. When she was asked: “What can you think of that is hard?” the gorilla signed “rock” and “work”. She also once tied her trainer’s shoelaces together and signed “chase”.

But what about other members of the animal kingdom – do they have funny bones? Marc Bekoff at the University of Colorado, Boulder, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and author of The Emotional Lives of Animals, believes they do. In fact, he thinks we are on the cusp of discovering that many animals have a sense of humour, maybe even all mammals.

Let’s go tickle some rats

A similar sentiment inspired psychologist Jaak Panksepp to enter his lab at Bowling Green State University in Ohio one day in 1997 and tell undergraduate Jeffrey Burgdorf: “Let’s go tickle some rats.” The lab had already discovered that its rats would emit unique ultrasonic chirps in the 50 kilohertz range when they were chasing one another and engaging in play fighting.

Now the researchers wondered if they could prompt this chirping through tickling. Sure enough, when the researchers began poking at the bellies of the rats in their lab, their ultrasonic recording devices picked up the same 50 kilohertz sounds. The rats eagerly chased their fingers for more. Soon, as the media trumpeted the existence of rat laughter, people the world over were opening up their rat cages and engaging Pinky and Mr Pickles in full-scale tickle wars.

We met Burgdorf at his office at Northwestern’s Falk Center, where as a biomedical engineering professor he has continued his rat-tickling efforts. He was cautious, however, about overselling what is happening with his rodents. “I don’t necessarily call it laughter, I call it a signal of positive affect,” Burgdorf told us.

His careful choice of words makes sense. Not everyone was convinced he and Panksepp had uncovered real rat laughter when their rodent-tickling activities first went public. But whatever you want to call it, Burgdorf, a quick-witted man with a boyish face and a sign on his office door that reads “Know It All,” has been obsessed with that strange rat noise he first heard in 1997.

Laughing pill

He seems to be on to something. While tickling isn’t always pleasant – thus the term “tickle torture” – in multiple experiments Burgdorf has demonstrated the rats’ 50 kilohertz chirping is only associated with positive experiences. For example, the rats only made this sound during rough and tumble play when the animals were of similar size. The vocalisations changed when one of the animals involved was much larger than the other, when it was no longer fun and games and instead looked more like bullying. And when given a choice, Burgdorf’s rats would push a bar to play a recording of the 50 kilohertz chirp as opposed to other rat noises, suggesting they had a preference for the sound.

Finally, when Burgdorf and his colleagues used electrodes, opiates and other manipulations to stimulate the reward centres of rats’ brains, the rats produced that same noise.

Whether you call it laughter or not, Burgdorf is convinced the ultrasonic noises signal the rats are experiencing happiness. Hence the “laughing pill” experiment: he and his colleagues are testing a new antidepressant medication on rats, to see if it makes them “laugh”, or chirp happily. If all goes well, Burgdorf believes the resulting medication could eventually be approved for humans. Rats, so often seen as a malicious pest, could end up making the world a happier place.

This article first appeared in Slate